Petitionary Prayer and the Parable of the Unjust Judge

During the past year, several news organizations revisited the circumstances surrounding what has been called the largest case of judicial misconduct in Pennsylvania history. A judge in a county juvenile court, during a period lasting approximately five years, imposed harsh sentences on an estimated 2,500 minors for offenses as small as mocking an assistant principal or trespassing in a vacant building. When a law firm started investigating, they noticed that over 50 percent of the children who appeared before the judge lacked legal representation, and about 60 percent of these children were removed from their homes to be placed in two private, for-profit juvenile-detention facilities. Eventually, it was discovered that in return for these placements, the judge had accepted large amounts of money from a facility co-owner and developer. The judge was arrested, removed, ultimately found guilty of several federal crimes. In the wake of the scandal, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court vacated all the sentences, dismissed the cases, and ordered the records to be expunged. Of course, much damage already had been done, and the lives of many teenagers were changed forever.[1]

It’s natural to feel outrage about this story. If you do, then you are in a good position to understand Jesus’ Parable of the Unjust Judge.

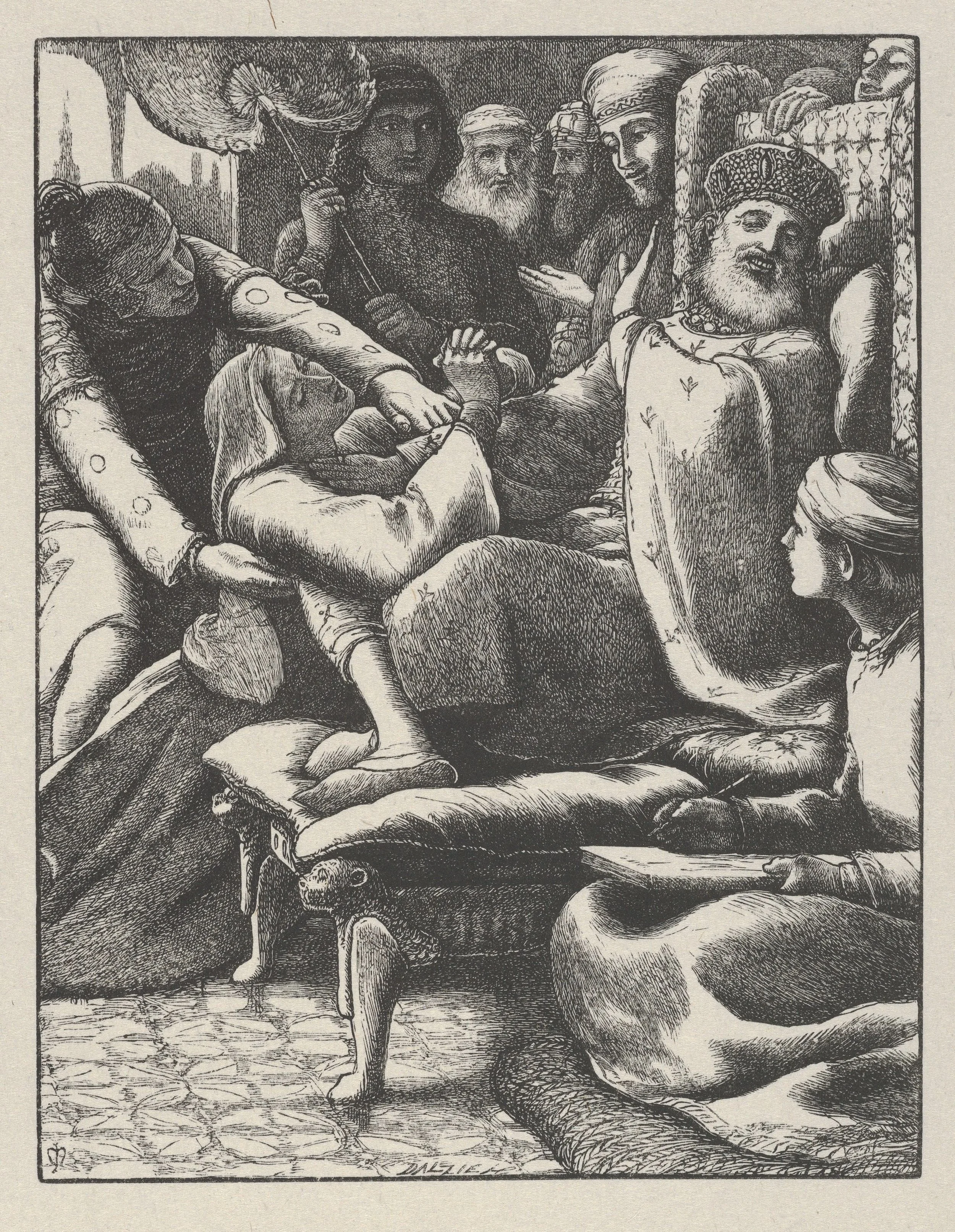

The disciples to whom Jesus told the story, and the audience for whom Luke retells it, both understood that justice in first-century Palestine could be arbitrary. Many who administered law were primarily interested in maintaining order and protecting property for the wealthy and well connected. Many on the lower rungs of the socio-economic ladder, like the children in the Pennsylvania juvenile court, felt neglected by the judicial system.

It’s possible to come away from reading this parable with more than one lesson, depending upon your understanding of the parable’s boundaries.

There are those who say that if you want to get at the core message, as originally told by Jesus, then confine your reading to verses two through five of chapter eighteen.[2] In this narrow reading, the focus is upon the widow’s repeated visits, and the judge’s final capitulation to her nagging request. The message is a lesson in perseverance, in bringing prayers to God again and again in the belief that enough repetition will finally bring the desired result. This line of interpretation is captured well in the words of one elderly minister, who said, “Until you’ve stood for years knocking at a locked door with bloody knuckles, you don’t really know how to pray.”[3]

If you open your field of vision just a bit wider, and read verses one through eight (the way I’ve read it for you) then you begin to understand how Luke frames Jesus’ words in order to help his audience understand Jesus’ purpose. In this reading, Luke is telling us that Jesus uses a common rabbinical principle: arguing from lesser to greater. In other words, if even a scoundrel judge responds to a pain-in-the-neck woman, how much more will a just God answer the prayers of God’s chosen ones? According to this reading, the parable’s message is a lesson in God’s good character meant to hearten the reader for the practice of prayer.

It’s possible to open the field of vision still wider. Some suggest that we should read the parable in light of the chapter that precedes it. Jesus’ words in chapter seventeen are what biblical scholars call “eschatological discourse,” or teaching about the end times. Some scholars say that Jesus’ parable makes most sense in relation to his teaching about the end times. In that larger context, the widow’s request “Grant me justice …” is like the longing of the disciples for God’s justice. In Jesus’ time, they’re only beginning to feel it. When Luke pens his gospel, the feeling is widespread. This is the time between the first coming and the second coming, the time when disciples are encouraged to live in hope that the present reality will give way to a new and better future.

Living in a deep and persistent Christian hope is at the root of a story told by my former preaching professor Tom Long.[4]

Mother Theresa of Calcutta was on a mission to raise funds to build a hospital for AIDS patients. In this effort she contacted Edward Bennett Williams, a famed philanthropist and trial lawyer, after whom the Georgetown University law library is named. Williams begrudgingly accepted the appointment, telling a colleague, “AIDS is not one of my favorite diseases.” Before the meeting took place, Williams already had decided he would listen politely, but then send Mother Theresa on her way with a polite but firm “no.”

The meeting took place; Mother Theresa explained her purpose. She asked for financial support, and received the answer “no.”

“Let us pray,” said Mother Theresa, folding her hands and bowing in prayer. Williams and an attorney friend looked at one another, but they also bowed their heads and prayed. After she said “Amen,” she went through the request again. Again Williams responded with a polite but firm “no.”

“Let us pray,” said Mother Theresa, bowing her head and folding her hands again. She prayed again. Again, she launched into her request. Williams finally relented, and agreed to draft a check.

Mother Theresa gives us an example of prayer flowing from deep and persistent Christian hope. It’s praying forward to a time when the weak and vulnerable are treated with the same fairness and generosity as the strong and wealthy. It’s praying forward to a time when, by God’s grace, a child in a war zone no longer dies for lack of medical treatment, food, or clean water. It’s praying forward to a time when, in the choice phrase of J.R.R. Tolkien, “what should be shall be.”[5]

Mother Theresa is gone now, of course. It’s up to new generations to hear Jesus’ challenging questions, and embody the mission to be his voice, hands, and feet to bring good news to a weary and broken world. “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?”

One of my colleagues in ministry is Cathi King, a Presbyterian pastor in southeast Michigan. Long before her call to ministry, Cathi’s future husband Andy was one of my college roommates. I co-officiated their wedding in 1988.

This past week, Cathi wrote about her experience of hosting about sixty second graders from the nearby school. Every year, she gives them a historic tour of the church building. The kids have started referring to the church as “the Jesus-and-God museum,” which Cathi finds interesting and a little disturbing.

Cathi writes that she always receives wonderful questions. Many of these children don't go to church and don't know why people do. “And this year, the last little boy in the last group of students asked: ‘What is church for?’”

The juxtaposition of that question with Jesus’ question is something I’ve been thinking about ever since. “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on the earth?” It’s up to us to pray and work toward a new and better day.

NOTES

[1] One summary may be found at https://jlc.org/luzerne-kids-cash-scandal accessed 15 Oct. 2025.

[2] See comments by Joseph A. Fitzmyer, The Gospel According to Luke X-XXIV, Vol. 28A in The Anchor Bible, Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983, pp. 1175-1178.

[3] R. Wayne Stacy, as quoted by Steven Mowery, in “Sermon Reviews,” Lectionary Homiletics, 17 October 2004, p. 29.

[4] The story about Mother Theresa and Edward Bennett Williams is recorded by William Willimon in Pulpit Resource, 18 Oct. 1998, pp. 13-14.

[5] Quoted by Thomas D. Parker, “Prayer in God’s presence,” The Christian Century, 29 Jan. 1997, p. 101-102.

READ MORE, https://www.fpcedw.org/pastors-blog